God’s Voice Calls the Hungarian People to Csíksomlyó

Translation of an article originally published in Hungarian by Magyar Jelen on June 15, 2025 by Tamás Lipták.

There’s something oddly compelling, perhaps even exciting, about the fact that we set off for Transylvania the day after the 105th anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon. This was already my fourth trip to Székely Land this year. But we didn’t come as guests. We came on a pilgrimage, to a land that, for all intents and purposes, is still unmistakably Hungarian.

Much has changed around us in the 21st century. Even the concept of pilgrimage has evolved, and to be honest, it now happens under much more comfortable conditions than it did decades or centuries ago. Still, it’s not the external aspects that matter most, but what we experience within. One might achieve a tremendous physical feat, and yet the soul may remain untouched. At the same time, it’s possible to quietly sink into reflection while gazing out the window, watching the land rise and bend, growing more wooded and winding as we approach the eastern ranges of the Carpathians.

Hungarian Stops in the Partium

Our first real stop was in a flatter region, just before reaching the hills, in the city of Szatmárnémeti. We parked in the shadow of old concrete apartment blocks, remnants of socialism that stand like monuments to a past ideology, and walked to the city’s main square, only a few minutes away. There we met with local friends and admired the beautifully renovated square and its surroundings, restored with dignity befitting the city’s long history. The contrast with the looming communist-era buildings just a few hundred yards away were stark.

(Editor's Note: Partium is the historically Hungarian-inhabited region of Hungary that lies alongside Transylvania and includes the counties of Bihar, Szatmár, and Arad. These lands, like Transylvania itself, were inseparable parts of the Kingdom of Hungary but were unlawfully and unjustly torn away by Romania after the Treaty of Trianon.)

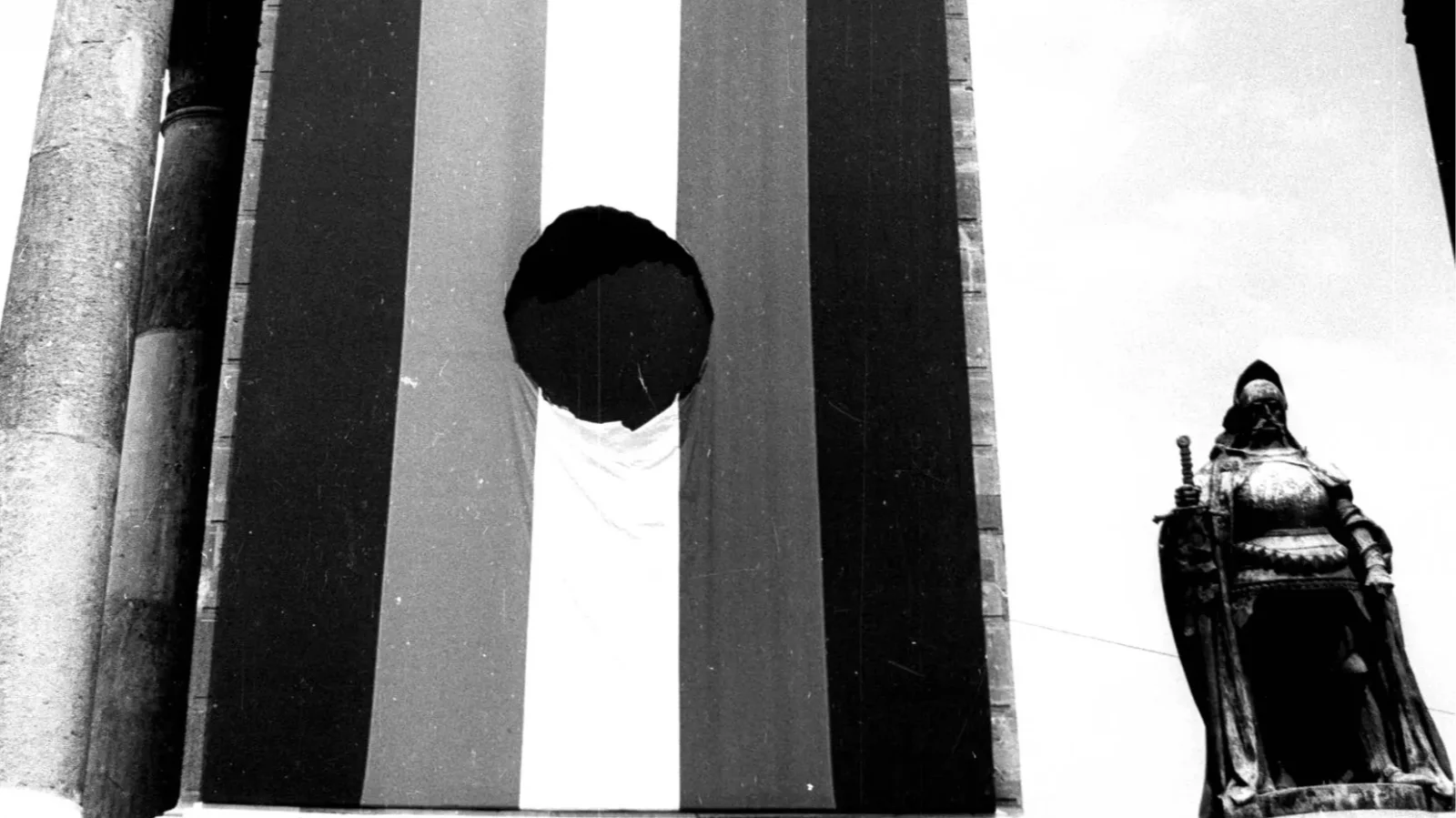

Roman Catholic Cathedral in Szatmárnémeti

There’s something that stirs the Hungarian heart in a particular way when looking upon buildings like the Great Church, also known as the Cathedral of the Ascension, where statues of Saint István and Saint László look down on us.

Statue of Saint László in Szatmárnémeti on the Roman Catholic Cathedral

Even football had its place. The local team, Olimpia Szatmárnémeti, had just been promoted to Romania’s second division, beating out Poli Temesvár. There’s talk of a new stadium too, something long overdue, given how badly time has treated the old one. Club president István Muresán said he was more worried about the stands holding up under the crowd for the decisive match than about the result itself. As it turned out, they held.

We didn’t have much time to linger, Muresán had to hurry to the team’s end-of-season banquet, and we still had a long road ahead to Kolozsvár, where we spent Thursday night, naturally among fellow Hungarians. Sightseeing had to wait until Friday morning, and by early afternoon, we were off toward Székely Land. We picked up another friend in Marosvásárhely, and with that, the car’s occupants now included two fans of Budapest’s Honvéd football club and two supporters of archrival Ferencváros. Somehow, the red-and-black coexisted just fine with the green-and-white, united under the red-white-green flag of Hungary.

The closed entrance of the Parajd salt mine

Exalted in the Saddle of Csíksomlyó, exalted in the deepest depths of our souls

We had hoped to spend more time in Parajd, but two things got in the way. First, we were running a bit late, and second, the Romanian Prime Minister was expected there that day. Since waiting around wasn’t an option, we made a quick stop to support local Hungarian vendors by buying souvenirs, then headed off to Székelyudvarhely. There, we watched the Hungarian national team’s loss to Sweden while enjoying grilled “mici”, a spiced meat delicacy prepared by our host, best washed down with a glass of pálinka, a traditional Hungarian fruit brandy.

We rose early Saturday to head for Csíkszereda, but even then, we couldn’t escape traffic. From the hill across the valley, we could already see the enormous crowd gathered in the Csíksomlyó saddle, making it easier to bear the frustration of likely arriving late. About half an hour before Mass began, we managed to park and set off toward the site. On the street, crowded with Hungarian pilgrims, a Gypsy boy was playing his accordion. Unfortunately, the only song he knew was “Bella Ciao,” a tune strongly associated with the extreme left. Several people told him this was not the place for that. He stopped playing.

But we didn’t stop. We kept walking, upward, both up the hill and into the depths of our souls.

There were tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, yet even among such a crowd, one could feel completely alone, if only for a moment of quiet reflection. That’s the essence of pilgrimage, the inner experience, possible only when we shut out the noise of the world.

More than three hundred thousand pilgrims of hope gathered this year in Csíksomlyó

The Voice of God Calling

Looking down from the slope, the world once again came rushing back. Hundreds of thousands of Hungarians, hundreds of thousands of souls, scattered across the landscape, many seeking shade beneath the trees from the blazing sun. I stood behind the altar, shaped like the triple mound from Hungary’s coat of arms, and listened to the sermon. “Say yes to love, say yes to life,” said Brother Alfréd György, a Camillian monk.

He spoke about the spiritual damage of profanity and urged us to carve out time each day for silence and prayer.

As I listened, my thoughts drifted, not out of boredom, but because what surrounded me pulled me into contemplation. Standing there among so many, yet feeling alone, I asked myself, what is the call that brings all these Christian Hungarians here, year after year? Where does this voice come from, one that draws us to say yes to life, yes to love? The answer is simple.

Over 300,000 Hungarians answered the call of God’s voice, a voice offering hope. Many traveled hundreds of miles to join this pilgrimage of hope.

These and many other thoughts raced through my mind, not only about Csíksomlyó but also about Budapest, Hungary, Hungarian identity, the past and the present, and the people who, one way or another, have been or still are part of my life. Some of them stood just a few feet away from me, others farther off. With some I ran into completely by chance on the hillside, with others I had arranged to meet there intentionally. Responding to God’s call, we climbed the hill and stood in awe of the quiet movement around us, a calm only broken by hymns that filled the valley with a powerful yet unassuming and deeply familiar sound.

Genuine, Deep, and Worthy Pride

As I walked down with the flowing crowd, it occurred to me that some call it pride to parade through the concrete jungle in colorful yet dull and somber clothing amid soul-damaging noise. But here in Csíksomlyó, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians who honor their traditions and openly profess their faith experienced God’s miracle within their souls and, to some extent, in the outside world as well. There is no question which of these two events offers greater reason for genuine pride, even if it does not need to be dressed up in a loud, flashy display for the sake of spectacle.

The Csíksomlyó pilgrimage does not boast, does not impose itself on others, and expects nothing from those who see the world differently. It simply exists and works. This nourishes true hope and gives cause for dignified, genuine pride.

It wasn’t until later, sitting on the terrace of a restaurant in Csíkszereda, that I realized how badly the sun had burned my skin. Suddenly, I understood why so many had sought shelter in the trees. I didn’t mind.

Hundreds of thousands sang the Hungarian and Székely anthems in Csíksomlyó

The Momentum Ran Out

On Sunday morning, we visited Hargitafürdő, where one of our companions had a personal matter to attend to. We stopped by the local Pauline monastery there, where Father Botond kindly made himself available to us. After the experiences of Saturday, it was especially comforting to talk about the pilgrimage, faith, the Pauline order, and the monastery’s recently constructed buildings. Anyone traveling through the area should definitely take the time not only for conversation but also for a few moments of quiet reflection.

The Saint Stephen Church stands in a picturesque setting in Hargitafürdő

As the sun set and our journey came to a close, we visited Csíkszentsimon once again, much like last year, where history somewhat repeated itself. Somewhat because on the day after the 2024 Pentecost pilgrimage, the Agyagfalva Momentum team was once again guests in the village famous for its brewery. But while we saw no goals at all last year, this time there were six, all scored by the home side in red and white, yet their joy was far from complete. They needed more to claim the championship and due to goal difference, they had to settle for second place.

The old grandstand filled up nicely

Interestingly, all three teams on the podium, Székelykeresztúr Egyesülés, Csíkszentsimon, and Székelyudvarhely Golimpiakosz, finished with 28 points in that exact order. Agyagfalva Momentum had to settle for fourth place which may explain why there was no trouble this year between the two teams’ supporters. In the evening, we were guests at the year-end celebration in Agyagfalva. While this event is less connected to the Pentecost pilgrimage, these gatherings are nonetheless very important for maintaining strong ties between Hungarians in Hungary and those brethren beyond the border.

Csíkszentsimon finished second in the championship

In just five days, one experiences far more in Transylvania than any report could contain, and some moments perhaps are not meant for the public eye. You have to set out, go there, and live the moment. To listen to God’s voice, which calls us ceaselessly, and at the same time to extend a hand to our Hungarian brethren who, though separated by borders, remain closely bound by national consciousness even 105 years after the Trianon disgrace. It is this duality that has allowed the Pentecost pilgrimage at Csíksomlyó to grow into the greatest event of Hungarian identity, standing far apart from the intrusive darkness now cloaking Hungary’s capital in a false and garish spectacle of artificial pride.

Photos: Tamás Lipták / Magyar Jelen

Az X- és Telegram-csatornáinkra feliratkozva egyetlen hírről sem maradsz le!Mi a munkánkkal háláljuk meg a megtisztelő figyelmüket és támogatásukat. A Magyarjelen.hu (Magyar Jelen) sem a kormánytól, sem a balliberális, nyíltan globalista ellenzéktől nem függ, ezért mindkét oldalról őszintén tud írni, hírt közölni, oknyomozni, igazságot feltárni.

Támogatás