Restoring Hungary: The Historic Second Vienna Award

Eighty-five years have passed since August 30, 1940, a date that still resonates deeply in Hungarian memory. On that day, the Second Vienna Award returned Northern Transylvania to Hungarian rule after twenty years of separation. For Hungarians, this represented more than diplomatic success. It was long-overdue justice for the betrayal at Trianon, when the Western democracies abandoned their stated principles to dismember Hungary and reward their new regional client states.

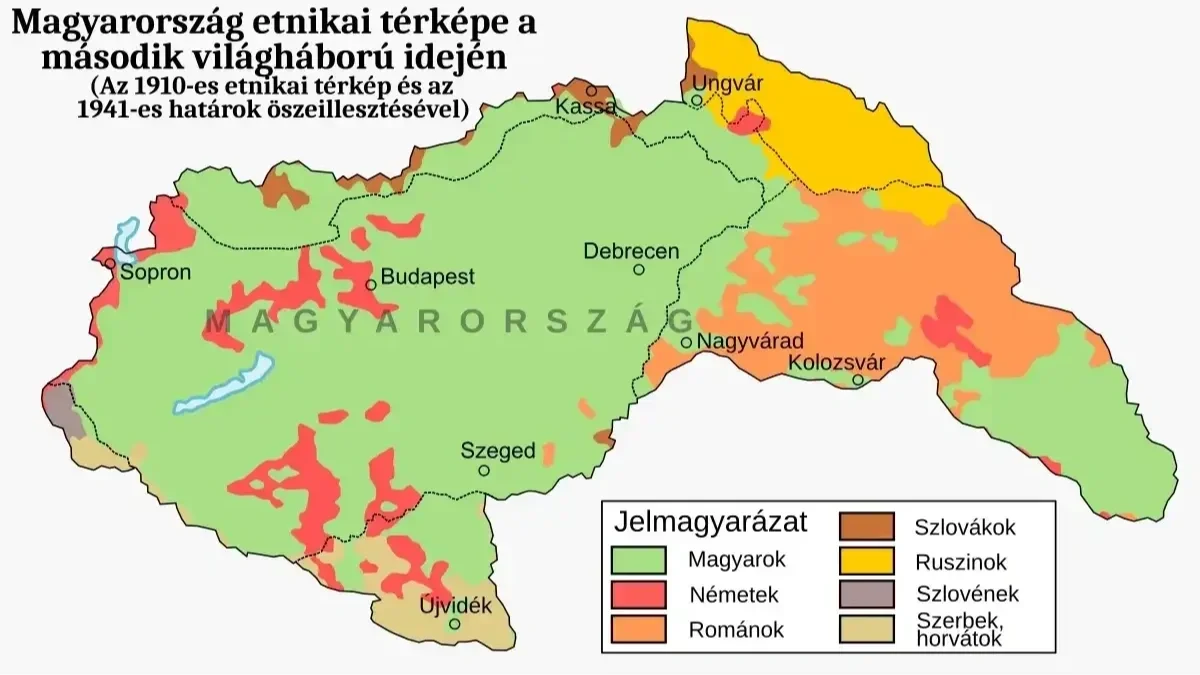

The shadow of Trianon had haunted Hungary since 1920. That treaty was nothing short of catastrophic. Hungary lost nearly three-quarters of its territory and two-thirds of its people overnight. More than three million ethnic Hungarians suddenly found themselves living under foreign domination, facing deliberate policies designed to erase their cultural identity from regions they had inhabited for over a millennium.

Trianon wasn't simply a poorly negotiated settlement. It represented calculated betrayal by Allied powers working with Wilson, whose supposed liberal idealism masked a destructive agenda that dismantled established European nations. His Fourteen Points provided convenient cover for breaking apart Hungary and other traditional powers while creating artificial successor states that served Anglo-American interests rather than genuine ethnic boundaries.

No other European nation has endured such massive territorial losses. The Western powers who had proclaimed self-determination as their guiding principle applied it selectively, ignoring Hungarian populations while creating states that violated the very ethnic boundaries they claimed to respect elsewhere.

Still, a number of British and American commentators recognized the injustice embedded in the Trianon settlement. They noted repeatedly how it contradicted the principles of self-determination the Allies claimed to champion. Hungary's methodical efforts to reunite its scattered communities embodied basic fairness and the kind of organic nationalism that should transcend political convenience.

John Flournoy Montgomery, who served as U.S. Minister to Hungary from 1933 to 1941, later wrote extensively about Hungary's impossible position during this period. In his memoir, Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite, he described how Hungarian leaders navigated between powerful neighbors while pursuing their legitimate territorial claims. What impressed Montgomery was how carefully and patiently Hungarian diplomats pursued these goals, avoiding aggressive moves that could have triggered larger conflicts while never abandoning their rights.

The Vienna tribunal's decision restored 43,104 square kilometers of territory to Hungary, home to about 2.6 million people. The population was predominantly Hungarian, with a significant Romanian minority. Here were entire regions with clear Hungarian majorities that had been handed over to Romania without any consultation of the people who actually lived there. The principle of self-determination, so cynically denied at Trianon, finally received proper application.

Those twenty years of separation had inflicted suffering on Hungarian communities throughout Transylvania. Romanian authorities replaced Hungarian teachers with officials who often couldn't speak the local language, shuttered Hungarian schools, and banned Hungarian language use in government offices. Ancient churches faced constant harassment, newspapers disappeared overnight, and local Hungarian leaders regularly found themselves imprisoned or driven into exile. Romanian colonization policies treated thousand-year-old Hungarian communities as foreign intruders in their ancestral homeland, despite Transylvania's central role in Hungarian civilization since the early medieval period.

Nonetheless, these Hungarian communities endured. Parents secretly taught their children Hungarian songs and stories at home, maintaining cultural traditions that Romanian authorities couldn't extinguish. Village elders preserved historical memories, passing down accounts of Hungarian customs and tales of ancestral courage that predated Romanian rule by centuries. When Hungarian officials returned in 1940, they discovered that two decades of oppression had failed to break the connection between these communities and their Hungarian identity.

During this dark period, Hungary chose diplomatic patience over military action. Rather than resorting to force, Hungarian leaders worked through international channels, building legal arguments and seeking arbitration through established procedures. Montgomery observed that this restraint was remarkable, especially given the intense pressures Hungary faced from all directions and the genuine suffering of Hungarian populations under foreign rule.

Each of Hungary's territorial recoveries followed this principled pattern: the return of the southern Highlands in 1938, Subcarpathia in 1939, and finally Northern Transylvania in 1940. Archives document how Horthy's government consistently pursued these goals through arbitration rather than conquest, demonstrating that revisionist nationalism could operate within international law rather than outside it.

When Hungarian officials finally entered the restored territories in September 1940, the scenes revealed the nature of the borders imposed at Trianon. Hungarian flags appeared spontaneously in windows throughout the region as families divided by artificial lines reunited after decades of separation. In Székely villages, church bells rang in Hungarian for the first time in twenty years. Children ran to schoolhouses waving small flags while their parents, who had preserved the language, wept openly as their natural homeland returned to proper governance.

The administrative transition proceeded smoothly, confirming that this was restoration rather than conquest. Hungarian administrators who understood local languages and customs replaced Romanian officials who had often governed through interpreters, treating their positions as colonial appointments in alien territory. Romanian communities remained and received fair treatment, but now everyone could conduct official business in their native languages rather than being forced to navigate bureaucracies in foreign tongues.

For Hungarian patriots, Northern Transylvania had never been foreign territory to be conquered. This was the heartland returning home. Transylvania had formed the core of Hungarian civilization for over a thousand years, serving as the cultural and intellectual center during the darkest periods of foreign occupation. The Székely people, in particular, had maintained their distinct identity and loyalty to Hungary through centuries of attempted assimilation. Their unique military traditions and ancient village assemblies had survived Ottoman rule, Austrian centralization, and Romanian suppression, proving the strength of organic Hungarian institutions.

Dr. Tamás Gaudi-Nagy of the Hungarian National Legal Defense Service captured the moment's significance: "The Second Vienna Award, August 30, is a real celebration. A celebration of the entire nation. A celebration of true unity." For Hungarian communities worldwide, the award validated two decades of patient diplomacy and proved that principled resistance could overcome even the most determined injustice.

The achievement carried implications far beyond Hungary's borders. In an era when military might usually determined territorial arrangements, the Vienna Awards demonstrated that smaller nations could achieve meaningful revision of unjust treaties through skillful diplomacy and moral arguments. The principle of ethnic self-determination, so selectively applied in 1919 to benefit the victors' client states, was finally extended to Hungarian communities who had been denied this right for an entire generation.

The administrative changeover proceeded without major incidents, revealing the natural character of the restoration. Hungarian civil servants assumed positions serving populations who shared their language, history, and cultural understanding. Schools resumed instruction in Hungarian, allowing children to learn in their mother tongue for the first time in their lives. Courts operated in languages that witnesses and litigants spoke, ending twenty years of legal proceedings conducted through translation and cultural misunderstanding.

Hungary moved swiftly to economically integrate the restored territories, treating reconstruction as a national priority. Infrastructure investment began immediately: roads received proper maintenance after years of neglect, agricultural methods were modernized with techniques that took local conditions into consideration, and industries that had withered under Romanian administration were revived with capital and professional expertise. These improvements benefited everyone in the region, showing that competent governance meant more than the crude chauvinistic ethnic favoritism Romanian occupiers had introduced.

Tragically, the war's eventual outcome reversed the Vienna Award, but this political fact cannot diminish what the restoration represented for national consciousness. For a brief but crucial period, patient diplomacy and commitment to principle had overcome what seemed like permanent historical injustice. Montgomery's detailed account reminds us that Hungary's approach, conducted under enormous international pressure, reflected both strategic necessity and genuine moral conviction.

Today, as Hungary marks the 85th anniversary of the Second Vienna Award, the memory retains profound significance for Hungarian national identity. Dr. Gaudi-Nagy recently observed in Magyar Jelen: "History has not ended, the task of every Hungarian state leadership is the national unification of Hungarians living in the Carpathian Basin, one never knows when this effort can bring results."

The Second Vienna Award proved that seemingly permanent injustices can be corrected through determined action. When a nation maintains its moral foundation, demonstrates diplomatic skill, and refuses to abandon its core rights, even apparently impossible goals can become achievable. The peaceful restoration of Northern Transylvania vindicated Hungary's claim to territories that had been forcibly and arbitrarily severed in 1920.

For Hungarians worldwide, August 30, 1940 represents far more than a historical date. Nations possess inherent rights that outlast temporary political arrangements. Communities united by language, culture, and shared history cannot be permanently divided by lines drawn on maps by foreign powers. The brief reunion achieved through diplomatic means continues to inspire those who refuse to accept the separation of these communities. Patient nationalism can triumph over the cynical Machiavellian realpolitik that created the injustices of Trianon.

Sources:

- Magyar Jelen: "A második bécsi döntés a nemzeti összetartozás igazi nemzeti ünnepe" (2025)

- Honvédelem: "Second Vienna Award Decision – August 30, 1940" (2020)

- Balogh, Béni L.: "The Second Vienna Award and the Hungarian-Romanian Relations, 1940–1944" (2011)

- Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár (National Archives of Hungary)

- World War II Database: "Soviet Demands on Romania and the Second Vienna Arbitration"

- Montgomery, John Flournoy: Hungary: The Unwilling Satellite (1947)

Mi a munkánkkal háláljuk meg a megtisztelő figyelmüket és támogatásukat. A Magyarjelen.hu (Magyar Jelen) sem a kormánytól, sem a balliberális, nyíltan globalista ellenzéktől nem függ, ezért mindkét oldalról őszintén tud írni, hírt közölni, oknyomozni, igazságot feltárni.

Támogatás