The World’s First Two Constitutions: The English and the Hungarian

Adapted from an article originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Jelen on October 12, 2025, by Erika Vasvári.

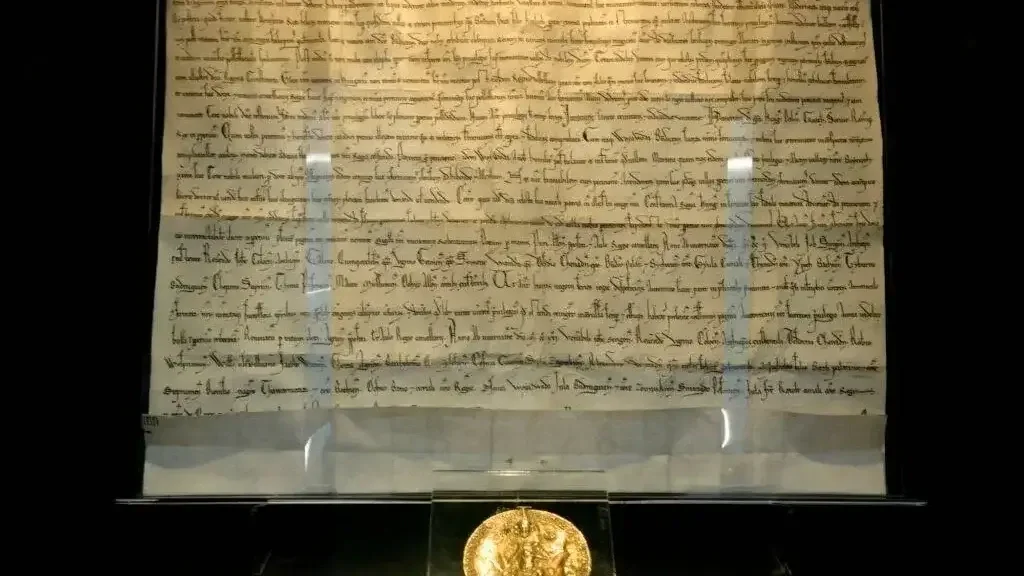

The Magna Carta Libertatum (Magna Carta, 1215) and the Bulla Aurea of King Andrew II of Hungary (Golden Bull, 1222) are among the earliest and most significant constitutional documents in European legal history. Both affirm the rights of the English and Hungarian nobility and establish that the king is subject to the rule of law. Yet the two charters reflect fundamentally different legal philosophies. The Magna Carta was rooted in feudal contractual relations, while the Golden Bull articulated a constitutional order founded on Christian and Roman-canonical legal traditions that developed independently, not as imitation but as a parallel expression of Europe’s Christian legal civilization.

This legal philosophy found concrete expression in one of the Golden Bull’s most essential provisions: the ius resistendi, or right of resistance. Its first written codification appears in Article 31 of the Golden Bull of 1222, though the principle itself long predated that formal articulation. The spirit and essence of this right of resistance reveal a continuity that endures to the present day, reflected in Article C of Hungary’s Basic Law, which preserves the ancient understanding that lawful resistance is not rebellion but fidelity to the divine and constitutional order embodied in the Crown.

Beyond its legal provisions, the Golden Bull also reinforced a distinctly Hungarian political community. By granting collective rights to the nobility, including semi-autonomous groups such as the Székelys, protecting ancestral lands through aviticitas, and enshrining the doctrine of the Holy Crown as the embodiment of sovereignty, it united law, morality, and national identity. These measures fostered shared responsibility within the political nation and safeguarded the kingdom’s territorial integrity, creating a community bound not by feudal hierarchy but by a collective legal and moral order that endured through the centuries.

The Hungarian right of resistance differed profoundly from that set out in the Magna Carta. It was far more comprehensive in both scope and constitutional significance. The Golden Bull granted all free Hungarians, individually and collectively, the right of resistance whenever the ruler failed to uphold its provisions. In England, by contrast, this right was reserved for only twenty-five barons.

This distinction reveals the essential character of Hungarian constitutional development. The principle of una eademque nobilitas (one and the same nobility) established that all nobles were equal regardless of wealth or holdings. This was not democratic equality in the modern sense but an organic expression of the unity, moral dignity, and responsibility of the political nation under the Holy Crown. It affirmed that the defense of law was inseparable from the defense of the homeland, and that every nobleman’s freedom arose from his belonging to the nation rather than from royal concession.

The Golden Bull therefore stands not as a feudal contract among unequals but as constitutional law governing the relationship between ruler and political nation. Unlike England’s Magna Carta, which limited royal power through baronial negotiation, Hungary’s charter expressed the nation’s collective conviction that authority itself must remain subject to the law of the Crown.

The Golden Bull set down in writing the constitutional order of Hungary, preserving and sanctifying the rights and customs that had endured since the founding of the Christian kingdom under King Saint Stephen of Hungary.

- It mandated annual judicial sessions in the royal city of Székesfehérvár, Hungary’s medieval capital and coronation site. This ensured that, according to Hungarian legal tradition, every person was entitled to a fair trial, while also affirming the ruler’s duty, or that of his representative the palatine (nádor), the kingdom’s highest-ranking official after the king, to administer justice. These törvénylátó napok (“law-seeing days”) formed the foundation from which the Hungarian Diet would later evolve, much as Parliament developed from the principles of the Magna Carta. Yet Hungary’s tradition did not arise from feudal compromise but from the Christian moral duty of kingship, first expressed in King Saint Stephen’s injunction that power must serve justice. By rooting justice in divine order and national custom, these assemblies affirmed that governance itself was a service to the nation.

- It laid the foundations of administrative law by defining the principal offices of the realm, including the lord palatine, chief justice, provincial governor (vajda), frontier commander (bán), count, and other dignitaries of state. In doing so, it established the framework of governance and the hierarchy of lawful authority. It also strengthened the Royal Council as an institutional check on monarchical power. Through these offices, the Crown embodied the harmony of order and freedom within the state, ensuring that no office existed outside the bounds of law. These were not merely instruments of administration but expressions of patriotic duty: to serve the Crown was to serve the national community entrusted by God.

- It developed the concept of public accountability by declaring that officials could act against others only in their official capacity, ensuring that no one could be deprived of liberty without a judicial verdict. This principle arose from Christian natural law and the conviction that all authority is bound by justice. Through this public legal order, the Golden Bull laid the foundation for institutions that preserved Hungary’s legal continuity through centuries of turmoil. In this way, the rule of law became inseparable from the nation’s own continuity. To this day, constitutional judges wear replicas of the Golden Bull’s seal on their robes, symbolizing this unbroken legal tradition.

- It established the sanctity of property and its system of legal protection through the principle of aviticitas, the inalienability of ancestral noble land. It stipulated that in the absence of a legitimate male heir or collateral successor, ancestral estates should revert to the Crown, with the exception of the daughter’s quarter (leánynegyed), the portion reserved for female heirs. This principle safeguarded not only individual property rights but the territorial integrity of the nation, ensuring that land could never be permanently removed from the Hungarian realm. It prohibited foreigners from possessing property within the country, a rule reinforced in Article 16, which forbade the cession or transfer of entire counties to foreign interests. This reflected the conviction that the nation’s soil formed part of its sacred inheritance under the Crown. Land was not an economic commodity, but a sacred trust handed down from generation to generation, a bond uniting the people with their country.

- It affirmed that authority over monetary and fiscal matters rested not only with the ruler but with the national assembly, limiting the fiscal abuses that had weakened the Crown and impoverished the realm. Fiscal restraint thus became a moral obligation, not an act of convenience. This early exercise of national oversight embodied the Hungarian conviction that economic independence was the foundation of political freedom and moral governance.

- By safeguarding the daughter’s quarter, ensuring marriage and dowry rights for daughters, and upholding the protections due to widows, the Golden Bull affirmed the Christian dignity of women as early as Article 4. Hungarian customary law on women’s property was not driven by abstract equality but by the moral discipline and familial order that sustained Christian civilization. In this spirit, family law expressed a broader truth, where the strength of the family mirrored the strength of the nation itself.

The Golden Bull's significance extends beyond its specific provisions to embody the constitutional theory unique to Hungary: the doctrine of the Holy Crown.

The Crown represented not merely a physical object but a legal person, the bearer of sovereignty itself. It symbolized the unity of God, king, and nation within an undivided and sacred legal order, affirming that sovereignty resided not in the monarch personally but in the Crown as the embodiment of the entire realm. This constitutional concept, without equivalent in Western feudal thought, made the Crown the unifying principle of Hungary’s legal order, encompassing king, nobility, and country as inseparable elements of a single whole. Through the Holy Crown, political, moral, and national identity were bound together into one living organism, a community of faith, law, and homeland.

Hungarian jurists and historians such as János Hajnik and Vilmos Győry have shown that the right of resistance expressed in the Golden Bull was the written confirmation of an older constitutional principle deeply rooted in Hungary’s Christian state tradition. Its spirit can be traced to King Saint Stephen’s Admonitions. As the kingdom’s founder and first Christian ruler, he established a state founded on law rather than arbitrary power. The same spirit of resistance appears in the Illuminated Chronicle, during the reigns of Peter Orseolo and Samuel Aba, and later in the Hungarian succession war of 1491 led by Kinizsi.

In each case, resistance arose not from disobedience but from loyalty to the moral order embodied in the Crown. Hungarian resistance was therefore always a national act, a defense of the community’s God-given order against the violation of its laws and honor. This right was never theoretical but invoked repeatedly: in 1401 against Sigismund, at the Diet of Rákos in 1505, in 1681, and during the constitutional crisis of 1790–91. The active exercise of this right of resistance shows that it was a living constitutional tradition, not a mere parchment principle. That it endured through centuries of occupation and absolutism confirms Hungary’s ancient conviction that liberty survives only where law stands above the ruler.

At the nineteenth Holy Crown Conference, Dr. Tibor Varga, legal historian and director of the Holy Crown of Hungary Foundation, observed that the Golden Bull reveals the active economic role of the Hungarian nobility in the pre-1526 era, before the catastrophic Ottoman victory at Mohács. The nobility engaged vigorously in commerce, viticulture, mining, and trade, forming an integral part of the kingdom’s economic life. Only during the Ottoman occupation, when Hungary was divided into three parts and faced an existential threat, did they retreat to their estates to defend their properties and preserve the territorial integrity of the realm.

That Hungarian constitutionalism not only survived but maintained continuity through one hundred and fifty years of partition and near-constant warfare attests to the strength of its foundations. The provisions of the Golden Bull helped preserve the country’s unity even during the Ottoman occupation, sustained by the legal coherence safeguarded in Werbőczy’s Tripartitum (1514), the comprehensive compilation of Hungarian customary law that codified and systematized the constitutional tradition. That same legal spirit later guided Hungary’s constitutional resistance under Habsburg rule, culminating in the Compromise of 1867, itself a reaffirmation of the Holy Crown’s principle of balanced sovereignty and lawful freedom. Through every trial, the legal order of the Crown remained the moral backbone of national survival.

The Golden Bull was reaffirmed and expanded in 1351 under Louis the Great, who confirmed its provisions while establishing additional constitutional principles, including noble tax exemption. This continuity demonstrates not stagnation but living development, a legal tradition sustained through commentary, application, and renewal, much like the English common law. Yet unlike England, Hungary’s continuity was upheld not by peace or isolation but by sacrifice and moral endurance amid foreign domination. Each reaffirmation was an act of national renewal, proof that Hungary’s law was not an artifact, but the living expression of a people’s will to remain sovereign.

Since international banking appeared in Hungary during the reign of King Andrew II, enhanced property protection became necessary. The tension escalated with the growing dependence on foreign financial support that accompanied royal fiscal mismanagement. The alienation of crown domains and the weakening of central authority were not mere administrative errors but the first signs of sovereignty yielding to outside interests. Warfare required substantial funds, and only foreign banks provided credit, so the state became impoverished through borrowing and forced to mortgage its territorial patrimony. The deeper lesson was moral as well as economic: a nation that entrusts its inheritance to foreign creditors endangers its wealth, its independence, and its moral integrity. Fiscal law was an expression of moral sovereignty, affirming that a nation ceases to be free the moment its wealth and land fall under foreign control.

"Countries are lost through debt, never won." This enduring lesson, which the framers of the Golden Bull already understood, remains valid to this day.

It reflects the hard truth of history: the subordination of national assets to foreign finance has always marked the beginning of decline. The preservation of sovereignty therefore demands constant vigilance against the erosion of territorial and fiscal independence. Hungary’s constitutional tradition recognized that freedom cannot coexist with indebtedness to foreign actors, for debt is the most insidious form of conquest. This conviction, born of centuries of trial, remains central to any true understanding of ordered liberty grounded in responsibility and faith. In the Hungarian mind, liberty has never meant individual license but the survival of the national community as a moral and political entity under God.

The Golden Bull stands as a monument to Hungarian constitutional achievement; a work of legal and moral architecture developed not in imitation of Europe but as a distinct path within its Christian civilization. While England faced no Mongol invasions or Ottoman armies at its gates, Hungary maintained constitutional order while serving as the bulwark of Christendom. Western historiography long regarded the Golden Bull as a reflection of the Magna Carta, yet in truth it arose from Hungary’s own Christian legal genius and remains one of Europe’s oldest surviving expressions of constitutional order. That this tradition has endured for eight centuries, finding expression even in modern Hungary’s Basic Law, testifies to the wisdom and foresight of those who gathered at Székesfehérvár in 1222.

The Golden Bull reminds us that Hungary’s liberty was never granted by rulers but born of faith, law, and the unbroken will to preserve the nation’s divine order. In this sense, the Golden Bull is not merely a legal text but a declaration of national being, the enduring testament that Hungary’s freedom and identity are inseparable, and perhaps Europe’s earliest constitutional expression of the national idea that the moral and political sovereignty of a people can be enshrined in law.

Note: The English version draws additional references from the nationalist–Christian school of Hungarian historiography represented by János Hajnik, Vilmos Győry, Pál Teleki, and Gyula Szekfű.

Mi a munkánkkal háláljuk meg a megtisztelő figyelmüket és támogatásukat. A Magyarjelen.hu (Magyar Jelen) sem a kormánytól, sem a balliberális, nyíltan globalista ellenzéktől nem függ, ezért mindkét oldalról őszintén tud írni, hírt közölni, oknyomozni, igazságot feltárni.

Támogatás